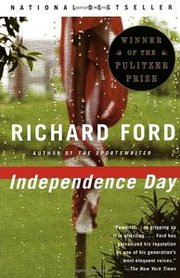

Everyone knows the Fourth of July is the beginning of the end anyway, so it feels no less fitting to have finished Richard Ford's second Bascombe novel a week before Labor Day than it would've had I read it over the July 4th weekend, as I'd originally promised David Goldfarb. In Independence Day, Frank Bascombe of The Sportswriter is still divorced but no longer profiling football players for a glossy magazine in New York (i.e. Sports Illustrated). It's 1988 and he's now a residential real estate agent in his adult hometown of Haddam, New Jersey, full of wisdom on home-shopping, -thinking, and -buying that has me more convinced that ever that renting is the way to go: "Buying a house will, after all, partly determine what they'll be worrying about but don't yet know, what consoling window views they'll be taking (or not), where they'll have bitter arguments and make love, where and under what conditions they'll feel trapped by life or safe from the storm, where those spirited parts of themselves they'll eventually leave behind (however over-prized) will be entombed, where they might die or get sick and wish they were dead, where they'll return after funerals or after they're divorced, like I did...Sometimes I don't understand why anybody buys a house, or for that matter does anything with a tangible downside." If 1988 was an uncertain time, I can only imagine what Bascombe would make of 2011. (Fun coincidence: 2011 and 1988 align perfectly, with July 4th falling on a Monday.) After two 450-page novels, Bascombe is still something of an enigma to me, full of (like so many men in American fiction) private poetic musings but less-than-forthcoming conversation, mislabeled (according to him) by nearly everyone he meets. And he meets a lot of people. In the course of this book's three-day holiday weekend, he has substantial encounters with his angry mixed-race renters; a picky, middle-aged, white Vermont couple who've been looking to buy a home for months; the manager of a hot dog and root beer stand in which he is part-owner; his tall, beachfront dwelling girlfriend whose husband disappeared years prior; a black truck driver in a motel parking lot where someone has just been killed; his beleaguered, richly remarried ex-wife; his good-humored, over-achieving daughter; his depressed and possibly bipolar son; a party girl chef at a Cooperstown B&B; and his Jewish ex-step-brother who's done well for himself in the flight simulator business. Not to mention the several past relationships he meditates upon and the dozens of insubstantial encounters at pay phones across New Jersey, New York, Connecticut and Massachusetts, the details of which are recorded impressively, even at times ecstatically, but with a precision too precise to be believed. They frequently left me exhausted. Meanwhile, Frank keeps a running tally of all those false monikers: "In three days, I've been called a burglar, a priest, a homosexual, a nervous nelly, and now a conservative, none of which was true. (It was not an ordinary weekend.)" And yet it's hard to blame anyone for misunderstanding Frank, lodged as he is in his dreamy Existence Period, as even he himself admits. There's so much to take away from this East Coast holiday tour, but for now, it's the exquisite descriptions -- some of them plot-centered, many just generously observed -- that are staying with me. The darkened ocean on a Jersey shore. A preteen daughter flopped on a Connecticut lawn. A helicopter lifting off from a hospital in the Catskills. Parachuters descending upon a village green. Only a writer as confident and skilled as Ford would use "blameless" to describe the light on a day for which our narrator (rightly) feels himself to blame. It is the sort of perfect, surprising, moralizing word, one of many in this book, that together turn a story about the world in which we live into an original vision of that world -- a vision, like that of Bascombe's hero Emerson, well worth engaging.

3 Comments

Matt

8/30/2011 11:54:36 pm

OK, so I wasted a few minutes reading various lit essays and blog posts on Ford. I didn't have the patience to wade through the entirety of this too-enthusiastic, too-philosophical appreciation of the Bascombe trilogy (http://www.readysteadybook.com/Article.aspx?page=mitchelmoreonford), so I'll just excerpt the passage I found most interesting:

Reply

Matt

8/31/2011 12:41:05 am

Oh, and here's the inevitable James Wood verdict. Interestingly, he seems to prefer The Sportswriter. But there are some lovely appreciative sentences in this review:

Reply

Matt

8/31/2011 12:43:26 am

Part 2 of Wood's review (I got it through LexisNexis from a 1995 issue of the Guardian, so I can't just post a URL):

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Aboutauthor of The Violet Hour, reader, prodigious eater of ice cream Archives

June 2014

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed