Most of my professional perks come from my job. "There are cookies in the kitchen!" reads a common 2 pm email. But there are a few perks to being a freelance writer, too. Case in point: having reviewed a couple Graywolf books over the years, I now frequently get advance copies of new titles I wouldn't otherwise have known about, including, because of my apparently irrepressible love of all things Scandinavian, every novel having anything to do with Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, or Finland. The latest, Child Wonder by the Norwegian novelist Roy Jacobsen, came to me this summer, and in my post-Eurasian hangover, when I was still very much lusting for Cold War stories from northern climes, and feeling nostalgic for Siberia's vast miles of birch woods every time I looked at my Marimekko shower curtain, I picked it up and hoped to be transported. The book, which was published last month, did not disappoint. Child Wonder is a great read, the story of 9-year-old Finn and his single mother, scrimping by stoically in the working-class suburbs of Oslo, circa 1961, the era of the Berlin Wall and Finn's hero Yuri Gagarin. As the novel opens, Finn and his mom are redecorating their apartment. They are self-sufficient, and they are finally indulging in a little affordable luxury: Swedish wallpaper. But the IKEA dream requires a little extra cash, and soon they are taking on a lodger, a well-dressed young man who comes with a television as well as a much-valued education. Another interloper -- a half-sister Finn didn't even know he had -- arrives soon after, and before long, the "delicate balance" of Finn's family of two has been transformed forever. Jacobsen manages the double-voice of an adult looking back on his youth brilliantly, narrating entirely from the young Finn's incomplete perspective, but with strong, ironic dashes of the adult knowledge that's still to come. It's pretty hard to do both at once, but somehow, through long, breathless, multi-clausal sentences that speak both to childish exuberance and grown-up complexity, Jacobsen and his English translators Don Bartlett and Don Shaw pull it off. The book is completely transporting. I was in 1960s Norway -- a time of rapid social change -- the entire time, but I think my favorite aspect was less specific to Scandinavia or the 1960s, and more general to single mothers and only sons. As much as he is eager for certain adventures, Finn constantly mourns the changes he witnesses in his life, and Jacobsen roots this ambivalence beautifully in Finn's relationship with his mother, right down to the suddenness with which their arguments flare as a growing son learns more about his mom: "I don't understand what you're on about," I said, ill-humoredly, and went into my room to lie down on the bed to read in peace, a Jukan comic. But, as is the case with protest reading in general, I couldn't concentrate, I just got angrier and angrier lying there with my clothes on, wondering how long a small boy has to lie like that waiting for his mother to come to her senses and assure him that nothing has changed, irrespective of whether Yuri Gagarin has blown us all sky high. As a rule it does not take very long, not in this house at least, but this time, oddly enough, I fell asleep in the middle of my rage." I've been to IKEA numerous times, so I can fully picture that little wooden bed. The mother-son dynamic is somewhat less pre-fabricated -- but in these pages certainly no less real.

0 Comments

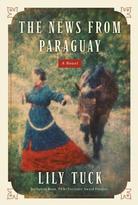

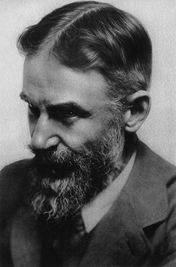

My review of Elissa Schappell's Blueprints for Building Better Girls and Lily Tuck's I Married You for Happiness is in the Philadelphia City Paper this week. Those 600 words only begin to describe how much I loved both books: the sharpness with which Schappell's characters flout social expectations even as they succumb to the rules, the elegance with which Tuck elides the laws of love and math. And I don't even like math! She makes me want to like math!  Honestly, I can't decide which these two writers know more about: writing women or writing sentences. They do both excruciatingly well. Read the books. (No, you can't borrow mine. Not right now, anyway, because I've already loaned them out. So just BUY THEM, for the love of god. Please.) And while you're at it, read their other books, too.  Schappell's first is the novel-in-stories Use Me, featuring Evie Wakefield, a character so brimming with selfhood she has to make a cameo appearance in Blueprints, too. It's about growing up in suburban Delaware; and trying to be an artist; and having a rich, promiscuous best friend; and breast feeding; and mourning the death of a glamorous, cancer-stricken father for years before he even dies. The book is all sexed up and devastatingly alive.  Tuck's previous novel, The News From Paraguay, which won the National Book Award in 2004, is a cool, unflinching story about the Irish mistress of a 19th century Paraguayan dictator, and a small, ambitious nation in the midst of civil war. I'm reading an older collection of her stories now, Limbo, and Other Places I Have Lived, and I'm still smitten. Wherever she wants to take me, I'll go. If only Schappell had more for me as well.  On the wall outside the bathroom at the New York Theatre Workshop: "This is the true joy in life, the being used for a purpose recognized by yourself as a mighty one; the being thoroughly worn out before you are thrown on the scrap heap; the being a force of Nature instead of a feverish selfish little clod of ailments and grievances complaining that the world will not devote itself to making you happy." (George Bernard Shaw) These lines are from the "Epistle Dedicatory" Shaw included with his script for Man and Superman. He is writing to Arthur Bingham Walkley, the English theatre critic who gave him the idea to write a Don Juan play, and Shaw's wide-ranging discussion eventually lands on this statement of artistic values, which he ascribes to the artist-philosopher. Turns out that Shaw's actually taking a stab at Shakespeare here, whom he calls a "fashionable author who could see nothing in the world but personal aims and the tragedy of their disappointment or the comedy of their incongruity" rather than the "constructive ideas" he wants artists to espouse. Hmm, well. Despite my initial surge of good feeling at these words, I can't completely agree with Shaw. This is good advice for living, and even for art as a vocation in general (a mighty purpose if ever there was one) -- but I tend to think that feverish, selfish little clods make for great characters, assuming they are human and emotionally alive. They can even work in service of stories that, among their many other effects, serve as critiques of our social world. (See: Shakespeare, of course, and Hardy and Woolf, and also Aleksandar Hemon, Lorrie Moore, Jonathan Franzen, Jennifer Egan, T.C. Boyle...and so on.) But I guess Shaw, the Fabian, is never very implicit in his arguments. Don't get me wrong, his attention to injustice and the exploitation of women and the working classes is admirable and often very finely rendered, but literature cannot always be about publicizing injustice and exploitation. Sometimes it has to be about personal demons -- which after all, help build all sorts of unjust worlds.  Anyway, this was great food for thought during the intermission of Elevator Repair Service's production of The Select. As an adaptation of The Sun Also Rises, it served up three and a half hours worth of the Lost Generation's most iconically feverish, selfish (and drunken) little clods. And a damned fine lot of them, too. See it before it's gone, New Yorkers. You've only got till October 23. |

Aboutauthor of The Violet Hour, reader, prodigious eater of ice cream Archives

June 2014

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed