|

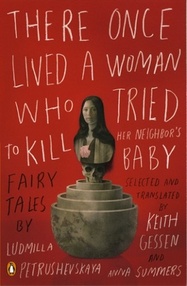

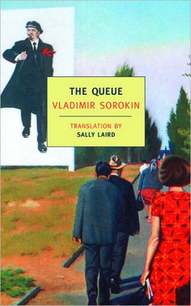

Summer destination: China-Mongolia-Russia. By train. We fly out a week from today, and the kind woman at Air Canada has assured me that we will have many movies to watch on the 13-hour leg from Toronto to Beijing. For the past few months, between online hostel-hunts and mini-meltdowns over confusing train timetables, I've been reading contemporary fiction from the countries we're visiting and cursing myself for not having already read more. (In the middle of this post, I dashed over to the Penn library to hustle up a couple more tales of contemporary China: Zhu Wen's I Love Dollars and Other Stories of China and Ma Jian's novel The Noodle Maker. More on those later...assuming I get to them.)  Amusingly, the Russian titles I selected -- Ludmilla Petrushevskaya's much-praised collection of "scary fairy tales" There Once Lived a Woman Who Tried to Kill Her Neighbor's Baby and Vladimir Sorokin's novel The Queue -- feature characters at a loss for information. Petrushevskaya's grief-stricken characters (mostly women) are just trying to survive in late-20th century USSR/Russia. In these short, spare, and off-kilter fables, they often find themselves in the middle of roads or other unfamiliar spaces, awoken as if from a dream, not knowing how they got there, or even, in some cases, who they are. Ghosts appear and food is rationed, and life changes dramatically, as in the title story, when the birth of a child poisons a relationship between two close female friends. Meanwhile Sorokin's cast of thousands is, as the title implies, waiting in line in Moscow sometime in the late 1970s. As they stand there in Godot-esque fashion, they speculate on the quality of the goods they're waiting for, how long they'll have to hang on to get them, and why it has to be this way at all -- sometimes drinking, sometimes sleeping, sometimes playing ball or making love, but all without surrendering their coveted places in line. The novel is composed of a steady stream of untagged dialogue, which sounds confusing but isn't -- at least no more than necessary for a novel about mass confusion. [*After writing this, I read Sorokin's post-Soviet afterword to the novel, in which he compares queues to church services. In the Russian Orthodox tradition parishioners stand, and the sentence "I stood through an all-nighter" can apparently also be translated as "I stayed through the all-night mass" or "I stood in line all night." The queue, says Sorokin, whose work was banned during the Soviet period, ritualized the collective body.]  It occurred to me at some point that Petrushevskaya and Sorokin are actually preparing me for my trip in more concrete ways than I initially imagined. On this adventure I'm about to take, I will be almost constantly arriving in places I don't recognize, frequently queuing to board trains and enter museums, and often unable to understand the systems that are operating around me. I will almost definitely have to ask the same question over and over, as Sorokin's characters do. Such is the nature of foreign travel for anyone who doesn't speak the language. The waking dream, and the beguiling order of things, are in some ways what we seek... Of course these themes are also classically Soviet and Russian, at least as far as American audiences have encountered them. (Or as far as my experience trying to buy train tickets on Russian language websites would suggest.) But now, after months of planning and years of hearing about Mother Russia, I'll finally get to experience it myself -- with The Brothers Karamazov coming along for the ride.

1 Comment

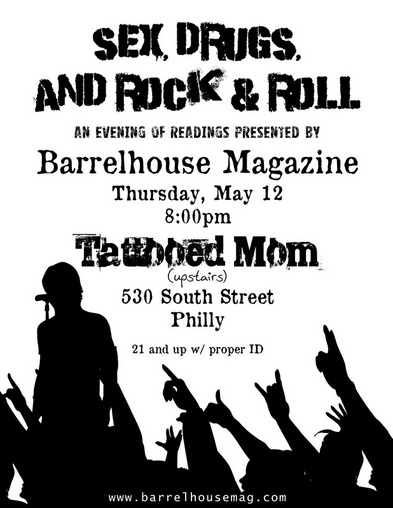

Thanks to Barrelhouse, I am going to be out of my depth (and maybe out of my genre) in this awesome line-up of writers tomorrow night: Elise Juska, Lee Klein, Tom McAllister, Stan McDonald, Christian TeBordo...and Katherine Hill? Should be fun, assuming I don't embarrass myself. Well, maybe even then.

|

Aboutauthor of The Violet Hour, reader, prodigious eater of ice cream Archives

June 2014

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed