Everyone knows the Fourth of July is the beginning of the end anyway, so it feels no less fitting to have finished Richard Ford's second Bascombe novel a week before Labor Day than it would've had I read it over the July 4th weekend, as I'd originally promised David Goldfarb. In Independence Day, Frank Bascombe of The Sportswriter is still divorced but no longer profiling football players for a glossy magazine in New York (i.e. Sports Illustrated). It's 1988 and he's now a residential real estate agent in his adult hometown of Haddam, New Jersey, full of wisdom on home-shopping, -thinking, and -buying that has me more convinced that ever that renting is the way to go: "Buying a house will, after all, partly determine what they'll be worrying about but don't yet know, what consoling window views they'll be taking (or not), where they'll have bitter arguments and make love, where and under what conditions they'll feel trapped by life or safe from the storm, where those spirited parts of themselves they'll eventually leave behind (however over-prized) will be entombed, where they might die or get sick and wish they were dead, where they'll return after funerals or after they're divorced, like I did...Sometimes I don't understand why anybody buys a house, or for that matter does anything with a tangible downside." If 1988 was an uncertain time, I can only imagine what Bascombe would make of 2011. (Fun coincidence: 2011 and 1988 align perfectly, with July 4th falling on a Monday.) After two 450-page novels, Bascombe is still something of an enigma to me, full of (like so many men in American fiction) private poetic musings but less-than-forthcoming conversation, mislabeled (according to him) by nearly everyone he meets. And he meets a lot of people. In the course of this book's three-day holiday weekend, he has substantial encounters with his angry mixed-race renters; a picky, middle-aged, white Vermont couple who've been looking to buy a home for months; the manager of a hot dog and root beer stand in which he is part-owner; his tall, beachfront dwelling girlfriend whose husband disappeared years prior; a black truck driver in a motel parking lot where someone has just been killed; his beleaguered, richly remarried ex-wife; his good-humored, over-achieving daughter; his depressed and possibly bipolar son; a party girl chef at a Cooperstown B&B; and his Jewish ex-step-brother who's done well for himself in the flight simulator business. Not to mention the several past relationships he meditates upon and the dozens of insubstantial encounters at pay phones across New Jersey, New York, Connecticut and Massachusetts, the details of which are recorded impressively, even at times ecstatically, but with a precision too precise to be believed. They frequently left me exhausted. Meanwhile, Frank keeps a running tally of all those false monikers: "In three days, I've been called a burglar, a priest, a homosexual, a nervous nelly, and now a conservative, none of which was true. (It was not an ordinary weekend.)" And yet it's hard to blame anyone for misunderstanding Frank, lodged as he is in his dreamy Existence Period, as even he himself admits. There's so much to take away from this East Coast holiday tour, but for now, it's the exquisite descriptions -- some of them plot-centered, many just generously observed -- that are staying with me. The darkened ocean on a Jersey shore. A preteen daughter flopped on a Connecticut lawn. A helicopter lifting off from a hospital in the Catskills. Parachuters descending upon a village green. Only a writer as confident and skilled as Ford would use "blameless" to describe the light on a day for which our narrator (rightly) feels himself to blame. It is the sort of perfect, surprising, moralizing word, one of many in this book, that together turn a story about the world in which we live into an original vision of that world -- a vision, like that of Bascombe's hero Emerson, well worth engaging.

3 Comments

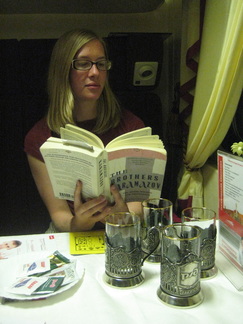

When the Spring/Summer 2010 issue of Ninth Letter rejudged the National Book Award of 1960, the new panel of writers -- Steve Almond, Sarah Shun-lien Bynum, Brock Clarke, and Michael Griffith -- awarded the prize not to the historical winner, Philip Roth's Goodbye, Columbus, but to Evan S. Connell's Mrs. Bridge, a novel I'd never heard of outside of a vague recollection of a Paul Newman-Joanne Woodward film I hadn't seen. The judges gave a panel on their process at the AWP Conference in DC last February, and the case they put forth for Mrs. Bridge so struck me that I immediately put it on my reading list. Here was a book praised for its endurance -- a story about an affluent and proper, but strangely listless, Kansas City housewife that nonetheless manages, in its crisp style and personal focus, to feel as much of our time as it is of India Bridge's 1930s or Evan Connell's 1950s. Months later, I devoured the book over a long August weekend in Vermont. The judges were right. Mrs. Bridge -- for India is a name from which she feels tellingly alien -- hardly knows herself. And yet, through Connell's 117 "chapterlets," many no longer than a page, we come to know her fears and preoccupations -- a distant but devoted husband, a trio of mysterious children with minds of their own, the embarrassment of having too much money and not enough to do -- which are, after all, the fears and preoccupations of many a modern, upper-class American. Of course there are discussions of laundresses, hats, and electric toasters that place the book in its time, but none of these details can really be accused of "dating" it. When the book happens upon a particular historic moment or reality -- the Nazi invasion of Poland, for instance, or de facto segregation of blacks and whites -- it does so in such a way that practically reintroduces those particulars to the reader of fifty years later, even as we know exactly where everything is headed. Like Salinger, Connell deftly mixes ironic detachment with unmistakeable tenderness in his portrait of this lady. The result is a character whose innocence is a genuine revelation. (Unlike, say, the underwritten Betty Draper in AMC's "Mad Men," a latter-day cousin who in the hands of January Jones is a genuine irritation.) This is not a novel that overturns our assumptions about bland, dignified surfaces. Mrs. Bridge feels as empty as she appears, but that's what makes her portrait so heart-breaking and (remarkably) not the least bit condescending. She knows something is wrong, but how on earth can she fix it? She doesn't really know what it is. In her passiveness, her inarticulateness, and her conservatism, she is as lovable as she is unforgivable. For more on Evan Connell, here's the excellent Mark Oppenheimer in The Believer. Great stuff here, particularly in the comparison to The Remains of the Day. Obviously, Mr. Bridge, that distant husband, is going be added to my list. On Dostoevsky, Virginia Woolf sells herself a bit short: "...the mind takes its bias from the place of its birth, and no doubt, when it strikes upon a literature so alien as the Russian, flies off at a tangent far from the truth." I had no other way to read Dostoevsky but as an alien (and I admit I often felt more alien reading it in translation than I did traveling through Russia without a drop of Russian beyond the constant, obsequious "spasiba") -- and yet, I had to read Dostoevsky. Eight weeks after starting The Brothers Karamazov on the train from Ulaanbaatar, in Central Mongolia, to Irkutsk, in deep Siberia, I finally finished the damn thing. It surely didn't help that Matt and I were sharing a single volume (the Pevear/Volokhonsky translation that people in the know seem to think is the truest) or that I spent more of my train time documenting every ordinary thing I saw, ate, and thought each day in my notebook. I'd visited two Dostoevsky museums -- one in Omsk, where he was imprisoned, and one in St. Petersburg, where he died -- before I'd read more than 200 pages of his final novel. And yet I persevered well after I was back in the States, flushing paper down the toilet and drinking water from the tap. Why? Because this was a failure I didn't want on my record? Partly yes, of course. But also because the book really does begin to overwhelm its reader after awhile. Even a reader who tends to shut down in the face of Christian philosophy and emotion.

And why does it overwhelm? Aside from the fabulous murder mystery that takes over the novel like a runaway troika somewhere around page 300? It overwhelms because the soul overwhelms. Here's Virginia again, in a delightful appraisal of what goes on in the pages of Dostoevsky: "The novels of Dostoevsky are seething whirlpools, gyrating sandstorms, waterspouts which hiss and boil and suck us in. They are composed purely and wholly of the stuff of the soul. Against our wills we are drawn in, whirled round, blinded, suffocated, and at the same time filled with a giddy rapture. Out of Shakespeare there is no more exciting reading. We open the door and find ourselves in a room full of Russian generals, the tutors of Russian generals, their step-daughters and cousins, and crowds of miscellaneous people who are all talking at the tops of their voices about their most private affairs....We are souls, tortured, unhappy souls, whose only business it is to talk, to reveal, to confess, to draw up at whatever rending of flesh and nerve those crabbed sins which crawl on the sand at the bottom of us." ("The Russian Point of View," The Common Reader) David Foster Wallace puts it this way: "The thrust here is that Dostoevsky wrote fiction about the stuff that's really important. He wrote fiction about identity, moral value, death, will, sexual vs. spiritual love, greed, freedom, obsession, reason, faith, suicide. And he did it without ever reducing his characters to mouthpieces or his books to tracts. His concern was always what it is to be a human being -- that is, how to be an actual person, someone whose life is informed by values and principles, instead of just an especially shrewd kind of self-preserving animal." ("Joseph Frank's Dostoevsky," Consider the Lobster) I can't say tracts are entirely absent from The Brothers K. Each of the three brothers -- Dmitri, Ivan, and Aloysha -- are people, 100% themselves, yes, but they also each represent a way of being in the world. Dmitri the way of desire, Ivan of reason, and Aloysha of love. Of course these ways are firmly rooted in the cultural-political climate of 19th-century Russia (which, as a deeply interested non-expert, Wallace summarizes nicely), but they are also rooted in Dostoevsky's own Christian purview. Often, when they speak their souls, these characters (along with the the dozens of other officials, ladies, and devils in the novel) speak their beliefs -- and their beliefs are nothing if not hysterical, discursive, and (partly owing to "brain fever," partly owing to essential humanness) maddeningly conflicted. It can be exhilarating but it can also, at times, get a bit tiring, and a bit confusing. Discussions of guilt turn to blows, which in turn, turn to discussions of the acceptability of turning to blows, which in turn, turn to idle chatter about the utility of learning French. And, of course, there's a whole lot about the separation of Church and State and loving God and all the rest. Sometimes, though, directness bursts through. Two maxims of Aloysha's mentor Father Zossima stand out. All are guilty, he insists. That, and life is paradise. (Or maybe it's just that Matt, the speedier, greedier reader, got to those maxims first, and had been wondering aloud about them for several days before they filtered down to me...But anyway...) These are beliefs we can grasp right away, and yet they are deceptively complicated, echoing and refracting throughout the novel in all sorts of interesting ways I'm still just beginning to understand. Or, to paraphrase George Steiner, Dostoevsky is a writer people have not just read and loved, but actually believed in. ("Could one say that one 'believes in Flaubert'?" Steiner asks. The answer, I guess, is no. Nuts.) From my alien, American, secular vantage, which much prefers the incorrigible, desperate binges of Dmitri to the endless grace of Aloysha (however heroic!), I can't say I really believe in old Fyodor. But I loved reading him, and I do think I know what Steiner means. |

Aboutauthor of The Violet Hour, reader, prodigious eater of ice cream Archives

June 2014

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed