|

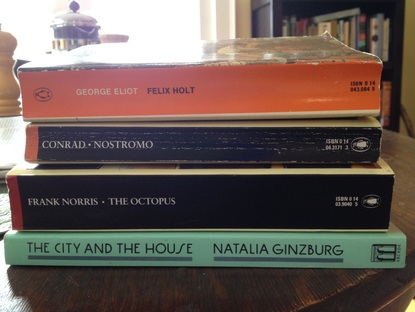

A visit to Commonwealth Books in Boston yesterday yielded four used paperback novels: George Eliot's Felix Holt: The Radical, Joseph Conrad's Nostromo, Frank Norris's The Octopus, and Natalia Ginzburg's The City and the House. To pass time on the T ride home, we read the first sentence of each, not expecting them to have much in common.  "Five-and-thirty years ago the glory had not yet departed from the old coach-roads; the great roadside inns were still brilliant with well-polished tankers, the smiling glances of pretty barmaids, and the repartees of jocose ostlers; the mail still announced itself by the merry notes of the horn; the hedge-cutter or the rick-thatcher might still know the exact hour by the unfailing yet otherwise meteoric apparition of the peagreen Tally-ho or the yellow Independent; and elderly gentlemen in pony-chaises, quartering nervously to make way for the rolling swinging swiftness, had not ceased to remark that times were finally changed since they used to see the pack-horses and hear the tinkling of their bells on their very highway." George Eliot, Felix Holt "In the time of Spanish rule, and for many years afterwards, the town of Sulaco--the luxurious beauty of the orange gardens bears witness to its antiquity--had never been commercially anything more important than a coasting port with a fairly large local trade in ox-hides and indigo." Joseph Conrad, Nostromo "Just after passing Caraher's saloon, on the county road that ran south from Bonneville, and that divided the Broderson ranch from that of Los Muertos, Presley was suddenly aware of the faint and prolonged blowing of a steam whistle that he knew must come from the railroad shops near the depot at Bonneville." Frank Norris, The Octopus "My dear Ferruccio, I booked my ticket this morning." Natalia Ginzburg, The City and the House Of course, each one was its own unique sentence -- just compare the lengthy Eliotness of Eliot with the epistolary brevity of Ginzburg -- and yet, in a way, they were all the same. Eliot and Conrad make explicit acknowledgment of changing times; Eliot, Conrad, and Norris offer a flavor of commerce and emerging technologies; and in all four, there a presumption, if not an outright declaration, of travel. Eliot has the coach-road, Conrad the port, Norris the county road and railroad, and Ginzburg the ticket. It's a reminder, however superficial (because after all, this was a subway game, and I haven't yet read any further), that fiction thrives on movement: of language, of action, of people. It's an old, facile dichotomy that there are two plots in fiction (a hero goes on a journey, and a stranger comes to town) which is a little too cute. And yet, when someone or something is going somewhere -- when a president heads to the Capitol to embark on another four years -- isn't it true that we can't help but wonder why, or how it will all turn out?

1 Comment

jhill

1/21/2013 02:17:27 am

A mother with unmarried daughters; a native son returning home, a train line that cuts off a farming district; unhappy families. Yes, each novel is a journey into life and deep experience, most ending badly because, well, what ending is there to lives expansively lived when not wittily expounded?

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Aboutauthor of The Violet Hour, reader, prodigious eater of ice cream Archives

June 2014

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed